- Title: Contemplations, Solutions to Problems of Ownership and Possession.

- Author: Arvindus.

- Publisher: Arvindus.

- Copyright: Arvindus, 2012, all rights reserved.

- Index: 201204101.

- Edition: html, first edition.

Etymology

The English 'ownership', derived through 'owner' from 'own',1 is thought to have originated from the old Teutonic 'aigan', meaning 'to possess'.2 To own is to possess. This word 'possess' can be traced back to the Latin 'possidēre'3 or 'possideō'. This word can refer to a holding in property but also to a holding in control and power. It may also refer to an absorption.4 This thought of absorption corresponds with the etymological meaning of 'ownership'. For in an ownership has a given been made one's own. In ownership has the owned been absorbed into the owner by which he may call it his own.

That in ownership the owned has been absorbed into the owner may sound a bit strange at first. For when we think of possessions we normally think of material objects. And it is clear that most of the material objects cannot be integrated in our own material body. The only material objects absorbable in our bodies concern food objects and perhaps organs in case of a transplant. How then can material objects be made our own?

Value and Identity

Value

How can material objects be made our own? To answer this question we first need to have a look at the value of an object. Objects are given certain values. These values are dependent on the usability of the objects. An object that serves no purpose, an object that cannot be used to reach a goal shall be given no value. This reaching of something by the use of an object should be understood in a wide sense. A watch receives its meaning and value through its purpose of knowing the time at any given moment. When the watch is broken and the goal of knowing the time cannot be reached anymore the watch becomes useless, meaningless and thus valueless. However it may still be given use, meaning and value when it is passed on as a heirloom. The bereaved may then use the watch as a reminder of times spent with the deceased. So the value of an object depends primarily on its usability. And the height of its value is primarily determined by the extend of its usability. The more usable and versatile an object is, the higher will its value be esteemed. It may be objected that the value of an object is also determined by its availability. This statement is correct on its own level, however the relation between availability and value can also be reduced to an object's usefulness. For nobody is in need of wearing ten watches. One watch serves its purpose. A high level of availability of one type of object only reduces its value due to the usability being decreased by that.

So the value of an object is primarily determined by its usability. This statement does need an addition. For an object is primarily determined by its usability for humans. A dead, hollow tree may provide a very useful nesting place for a woodpecker, however it is of not much use for a human. Thus a dead, hollow tree will not be valued very highly, no matter how useful it is for a woodpecker. So humans determine the value of an object on base of its usability for them.

Now it is true that woodpeckers among each other do value dead, hollow trees on their own instinctual level. Humans however do generally also function on an emotional and on an intellectual level. And it is also on these levels that they value the objects for their use. Human valuing of objects is not bound by instinctual impulses for use and not even by emotional tendencies but extends into mental valuing also. And at this mental stage has the usability of an object been processed into an idea of value. A value is a value idea. This idea then is being expressed among humans in the concrete price which the object is given.

Identity

Now it are not only objects from which ideas are induced. This is also done in the case of human subjects. Individuals tend not to interact with each other directly as individuals. They tend to cover their pure humaneness with a whole spectrum of identifications. They see themselves as English, Christian, carpenter and more of the like. And identifying thus they look at other individuals with contrasting identifications. They identify others as Indian, Hindu, cook, etcetera. Now this spectrum of different identifications is gathered in one idea about the regarded individual. And this idea is an individual's identity. An identity is an idea entity. And this idea then is being expressed among humans in a concrete name or unique number.

Now it is so that ideas can be absorbed into each other very easily. For instance the idea of a horn can be integrated very easily with the idea of a horse, resulting in the synthesized idea of a unicorn. This ease of integration of ideas stands in contrast with the difficulty of integrating material givens. Integrating a material horn with a material horse is quite an arduous task. Now as can be remembered was a similar difficulty discovered in integrating material objects with material bodies of individuals. Material objects cannot be absorbed into material human bodies. However ideas induced from material objects can be absorbed by ideas induced from material human bodies. Values can be absorbed by identities. Value ideas can be absorbed by idea entities. When this happens, when the value idea of an object is absorbed by an idea entity, then the object becomes in possession of an individual. However only in ideality and definitely not in reality. Possession and ownership are an integrated idea induced and maintained by and among humans.

Problems of Ownership and Possession

In the previous paragraph we concluded that possession and ownership are an idea induced and maintained by and among humans. Now induction of ideas is on itself not unproblematic. On the contrary. In an earlier contemplation was a problem defined to be 'an obstacle that keeps one from moving forward and that therefore is fit to be hit and destroyed'.5 And the goal of humans was in another contemplation thought of as the attainment of the metaphysical,6 which equals the realization of reality.7 So when the progress of a human towards the realization of reality is obstructed it can be considered to be a problem. And this happens exactly with the induction of ideas. Reduction, as has been contemplated before, surely leads one to reality, however induction does definitely not.8 It is not a problem when material givens are reduced to ideas (something which has been thematized for instance by the Greek philosopher Plato)9. However when material givens are induced to ideas human progress towards reality is halted and a problem occurs.

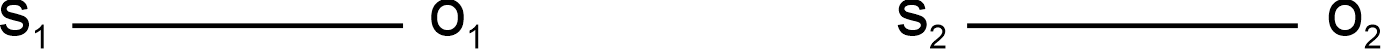

The above thought may be symbolized as follows. In figure 1 we see two material human subjects, s1 and s2, relating to two material objects, o1 and o2. Object o1 stands apart from subject s1 and object o2 stands apart from subject s2. The material objects are not integrated into the material subjects and the relation between subject and object is one of mere usage. The objects are being used by the subjects, but the first are not in possession of the latter. Figure 1 does not show a problematic situation.

Figure 1.

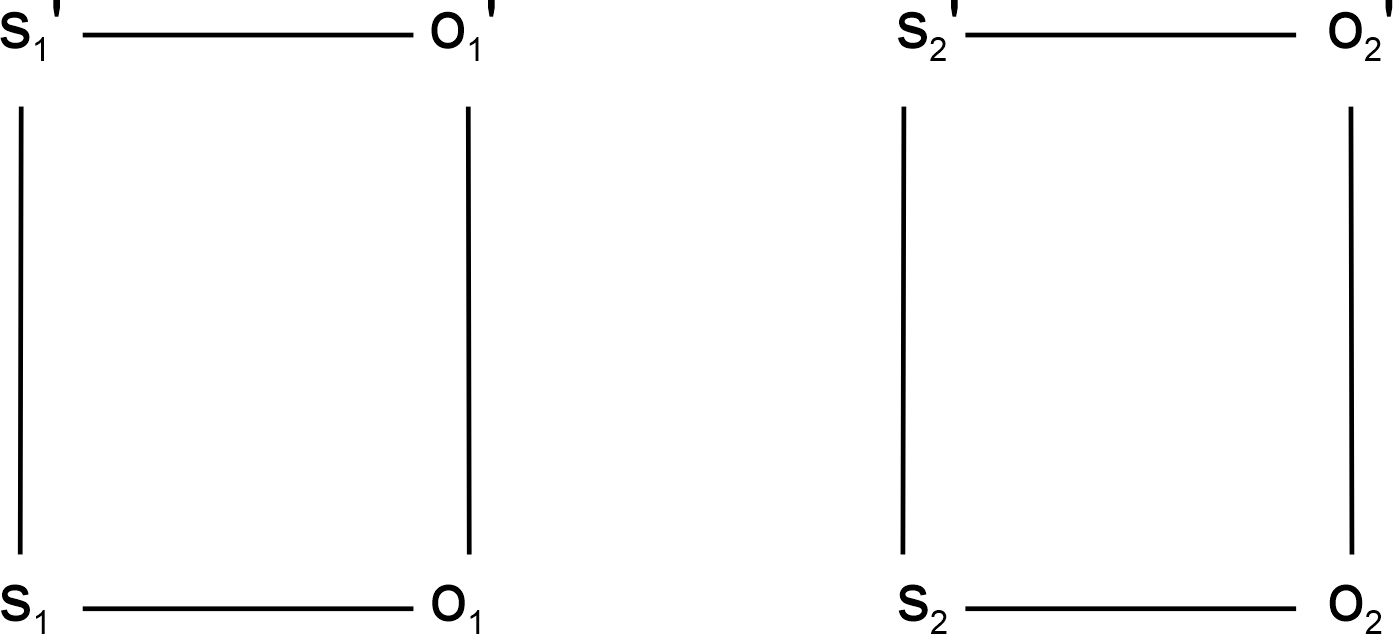

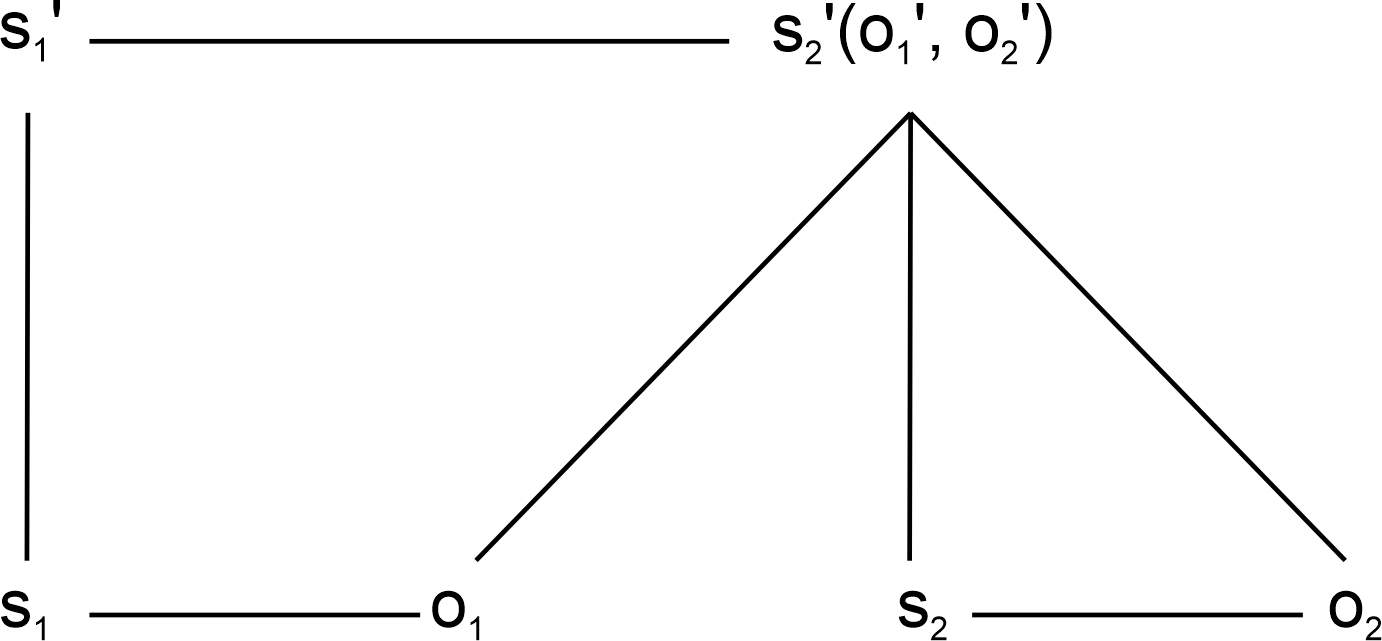

Figure 2 shows the emergence of the above mentioned problem. From the material human subjects are identities s1' and s2' induced and from the material objects are the values o1' and o2' induced. The objects are however not yet taken in ownership and possession by the subjects. We see the objects still stand apart from the subjects. Although in this figure identities and values are induced is the relation between subject and object still one of mere usage.

Figure 2.

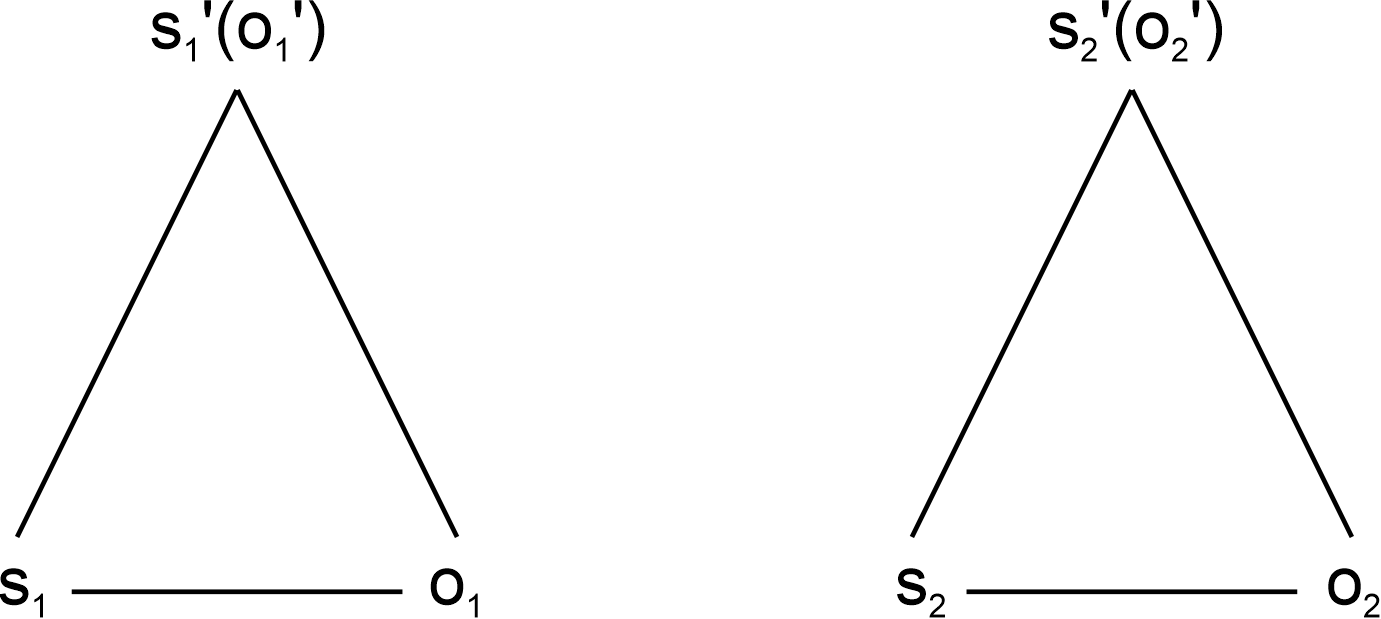

In figure 3 the taking in possession of the objects by the subjects takes place. The relation between the subjects and the objects on the material level shows that this is still one of usage, as was the case in the previous figures. Object o1 is still being used by subject s1, and the same goes for object o2 and subject s2. At the level of induced ideas however two integrations have taken place. At that level has value o1' been integrated in identity s1', and value o2' in identity s2'. And with these integrations have the two objects come in possession of the two subjects.

Figure 3.

With this does another problem arise. Previously did s1', o1', s2' and o2' one on one reflect s1, o1, s2 and o2. This kept reductions from the former to the latter relatively simple. Now have induced reflections of what is materially the case been entangled with each other. It is relatively easy to reduce the induced idea of a horn and of a horse to a material horn and a material horse. However to bring the idea of a unicorn back to the aforementioned is more complex because first an untangling must take place. A unicorn is no simple reflection of what is the case at the material level.

Now in the entanglements of values with identities is one subordinate to the other. This is also the case with for instance a unicorn. With a unicorn is the horn subordinate to the horse. The horn there is an attribute of the horse. And similarly is a value in ownership and possession subordinate to the identity with which it is entangled. Therefore the notations 's1'(o1')' and 's2'(o2')' are used; the values have become elements within the domain of the identities. Thus do ownership and possession also lead to an expansion of identity. This is again another problem. An identity is induced by a human individual and becomes what he identifies with. However this identity is a phantom and is not the reality of the individual's being. When thus this identity expands by gathering within its domain induced values of objects then the individual's illusion about his own being increases also. In popular speech such an enlarged identity is often called 'a big ego'. This is how possessions become part of one's identity.

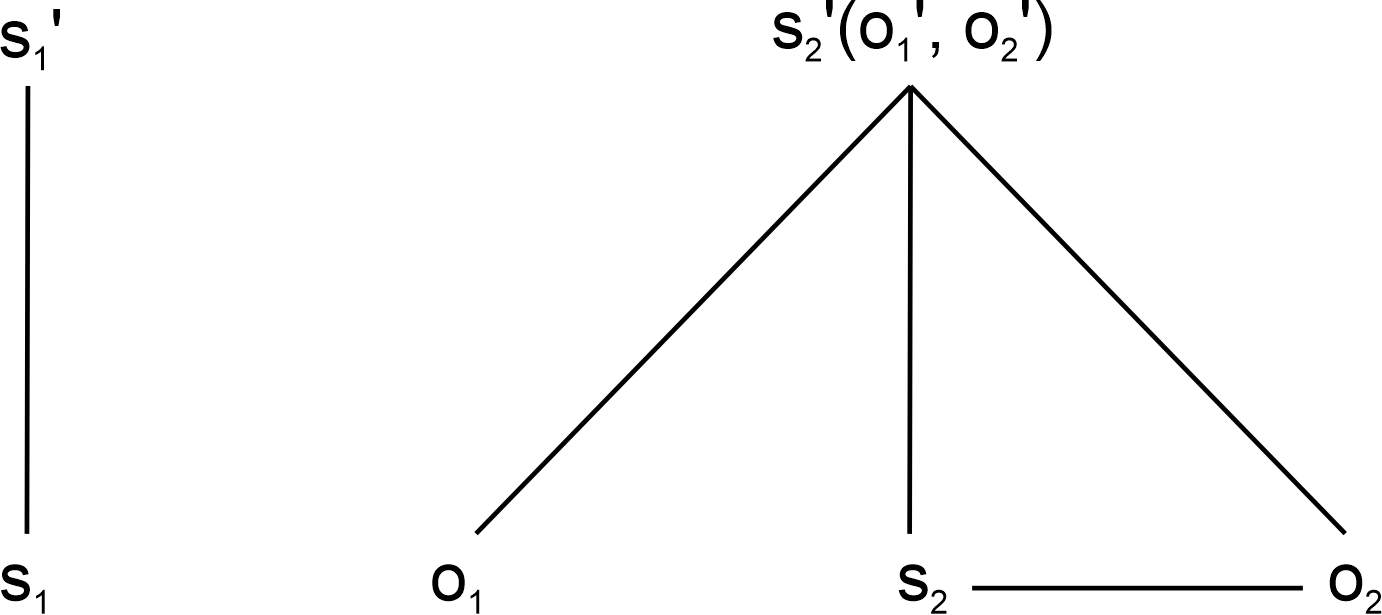

Still another problem occurs when induced values of objects are added to an identity's domain while the objects are not used by the corresponding subject. This we see symbolized in figure 4. Both the values o1' and o2' have been added to the domain of identity s2'. Now however have possession and use been unlocked from each other. Figure 3 showed an ownership in which the owned object was also in use by the regarded owner. Figure 4 however shows one subject owning no object while another one is owning two of which he uses only one. In this figure does object o1 only exist for the expansion of subject s2's identity. The prime relation of usage between a subject and an object has been exchanged for the growth of a subject's identity. And it is obviously problematic when the growth of an induced idea is given primacy over the more substantial relation between the two material givens of subject and object.

Figure 4.

Another problem occurring in figure 4 is of course the unequal distribution of objects for use between subjects. Subject s2 has ownership over two objects, but uses only one. Subject s1 owns no object and is thus unable to use any. And this way his material needs may not be met. This can be said to be a humanitarian problem.

Now this situation where subject s1 cannot make use of object o1 because its induced value is integrated in subject s2's enlarged identity is being settled in figure 5. In this figure is again a relation of usage between subject s1 and object o1 indicated. This however while o1 stays in possession of subject s2. In this situation has subject s2 given subject s1 permission to use object o1. Usually such permissions however come with a price. And this is indicated by the relation between s1' and s2'. For the usage of o1 by s1 does s2 demand a transference from identity s1' to identity s2'. This transference then consist of elements within s1' being transferred to s2'. Such elements may regard the values of objects being owned by s1 (regarding a transference of possession) but they may also regard elements that are induced into s1' by the process of identification. Having identified himself with Hinduism for instance, and with that considering himself a Hindu, may subject s1 be demanded to take a submissive stance towards subject s2, who thinks himself to be for instance a Christian. In this way then is the value of subject s2's Christian identity increased. And such a transference occurs as said in return for the usage of object o1 by subject s1. A good example here is the renting market for houses where one individual lets out his owned houses which are not in use by him to other individuals who do not have the possibility of owning a house for themselves.

Figure 5.

It shall be clear that in this way also a vicious circle is created. The more possessing subjects ever increase their possessions and the volume of their identity at the cost of the less possessing subjects, the more the latter become dependent on and submissive to the first. Those recognizing contemporary capitalism in figure 5 have been observing correctly.

Solutions to Problems of Ownership and Possession

Recapitulating the Problems

Let us start the present paragraph by recapitulating the problems that were encountered in the previous one. This may help the solutions to be up to the mark. As problems of ownership and possession we found:

- The problem of induction. Idea entities and value ideas are induced from subjects and objects to make possession possible. This is a problem because induction leads one further away from reality.

- The problem of entangled ideas. In ownership and possession are values entangled with identities. This results in complex ideas complicating reductions back to the greater reality of the material subjects and objects.

- The problem of enlarged identity. When values are integrated into identities by becoming part of the latter's domain, the latter's size is increased. Thus the illusion of identity is enhanced complicating again reductions.

- The problem of unequal distribution. When certain subjects own more objects than they use there are bound to be found subjects owning less objects than they need to use.

- The problem of renting. In renting does a subject give his owned but unused object in use to a non-owning subject in return for a transference of value from the identity belonging to the non-owning subject to the identity belonging to the owning subject. This increases the problems mentioned under 4, 3 and 2.

Solutions

In the previous sub-paragraph were the problems of ownership and possession in a condensed way enumerated. Under this paragraph shall solutions to the aforementioned problems be enumerated.

- Solution to the problem of renting. The solution to this problem is easy to find: Renting should be abolished from society. Abolishing renting will break the vicious circle in which the problems of unequal distribution, enlarged identity and entangled ideas ever increase. This solution should be conducted however along with the solution mentioned next. For if the present solution is conducted in isolation non-owning subjects will find themselves bereft of material needs.

- Solution to the problem of unequal distribution. In order to keep non-owning subjects from being bereft of material needs it should not be allowed for subjects to own more objects than they have in use. At the same time then should every subject be given the right of ownership over all needed objects. This will distribute objects more equally and fairly over subjects.

- Solution to the problems of entangled ideas and enlarged identities. The problems of entangled ideas and enlarged identities concern both the complication of reductions. Illusions hold sway where reductions are obstructed. The integration of values with identities is the cause of these two problems. Ownership and possession are the cause of these two problems. The solution to these problems is then the abolishing of ownership and possession.

- Solution to the problem of induction. Because the induction of ideas is at present part of human nature it will be extremely difficult to really abolish induction, which eventually however is the only solution to this problem. The only thing that can be done at present is the stimulation of those practices that help to overcome the induction of ideas. In another contemplation were mentioned practices such as detached, selfless intentional action and selfless detached concentrated contemplation.10 Detachment will reduce induced values and selflessness will reduce induced identities. Thus is the solution to the problem of induction the cultivation of detachment and selflessness.

Looking at the five problems of ownership and possession and to the four solutions for these problems it can be seen that problem 5 is the root of all other problems and that thus solution 4, offering a solution for the aforementioned root problem, is the most important of all. Any applied solution must be sided with the application of solution 4. If the root is not exterminated a poisonous plant may always grow new sprouts. At the same time however is this solution 4 the most difficult one to apply. The first three solutions may be applied with force on individuals by for instance the state. But solution 4 needs the voluntary consent of all individuals.

May thus all of us be led to detachment and selflessness.

Notes

- Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition on CD-ROM (v. 4.0), Oxford University Press, 2009, ownership, owner.

- Ibidem, own, a.

- John Ayto, Word Origins, The Hidden Histories of English Words from A to Z, A & C Black, London, 2005, p. 389.

- Oxford Latin Dictionary, Oxford University Press, London, 1968, p. 1410.

- 'Contemplations, The Problem of Self-Determination', Index: 201107261, The Problem of Self-Determination.

- 'Contemplations, A Setup for a Metaphysicratic Manifest', Index: 201204032, Anthropotelos.

- 'Contemplations, The Spiral of Realization', Index: 201109261.

- 'Contemplations, Reduction (and Pseudo-Reduction)', Index: 201004221.

- Richard Kraut, 'Introduction to the Study of Plato', in: Richard Kraut (editor), The Cambridge Companion to Plato, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge / New York / et alibi, 1999, p. 7.

- 'Contemplations, A Setup for a Metaphysicratic Manifest', Index: 201204032.

Bibliography

- 'Contemplations, A Setup for a Metaphysicratic Manifest', Index: 201204032.

- 'Contemplations, Reduction (and Pseudo-Reduction)', Index: 201004221.

- 'Contemplations, The Problem of Self-Determination', Index: 201107261.

- 'Contemplations, The Spiral of Realization', Index: 201109261.

- John Ayto, Word Origins, The Hidden Histories of English Words from A to Z, A & C Black, London, 2005.

- Richard Kraut, 'Introduction to the Study of Plato', in: Richard Kraut (editor), The Cambridge Companion to Plato, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge / New York / et alibi, 1999.

- Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition on CD-ROM (v. 4.0), Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Oxford Latin Dictionary, Oxford University Press, London, 1968.