- Title: Contemplations, Heidegger's Thought Symbolized.

- Author: Arvindus.

- Publisher: Arvindus.

- Copyright: Arvindus, 2014, all rights reserved.

- Index: 201404182.

- Edition: html, first edition.

- Original: Contemplaties, Heideggers denken gesymboliseerd, Index: 201404181.

§

The thought that Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) in his philosophy indicates to advocate is by many experienced as difficult to understand. To make this thought more graspable shall in this short contemplation his thought be symbolized with a simple figure. Hereby it should be taken in consideration that such a symbolizing does not find methodical connections with Heidegger's thought itself. The method in this contemplation could from Heidegger's thought be done with as 'thingly' ['dinglich'].1

With this mentioning of thingliness is already that given touched against which the whole of Heidegger's philosophy is pointed. For this can be shortly summarized in the words: "The Being of Beings »is« not itself a Being".2 Being is not a thing, but according to Heidegger has the Western philosophical tradition being always thematized as if it is a thing (namely a highest thing).3 Heidegger wants to break with that tradition and thematize being as being. But then what is being according to Heidegger? It can be stated that being for Heidegger equals phenomenality. After all being as alètheia [άλήϑεια] regards unconcealedness4 and phenomenality regards the revealed.5

This idea of phenomenality is in Heidegger's thought actually thematized as alternative for the subject-object relation of the classical epistemology. In that classic epistemology are first subject (human) and object (thing) posed as primary evidences after which a relation between those two is thematized through a secondary perception. Heidegger however places in his phenomenology the phenomenality as primary in which secondary the subject and object are contained. The subject and the object are in phenomenality, in being, equal-original [gleichursprünglich] present. Equal-original means that one is not the origin of the other. The perceived consists as such not by the grace of the perceiver and the perceiver not as such by the grace of the perceived. Both are equal-original contained in the primary given of perception. It is therefore also that Heidegger for the subject uses the term 'being-there' ['Dasein'].6 For the being-there is not an in itself closed perceiving thing but is always there. This means; he is always in the world; his being is equal-original with the being of the world.7

Now according to Heidegger there are in the basis two possible modes of being. There are the possibilities of an authentic and of an unauthentic being. In an authentic being does being unclose itself as being and in an unauthentic being uncloses being itself as a thing. Important in this to consider is that also in an unauthentic being the authentic being is present, be it in a by the unauthenticity concealed way.8

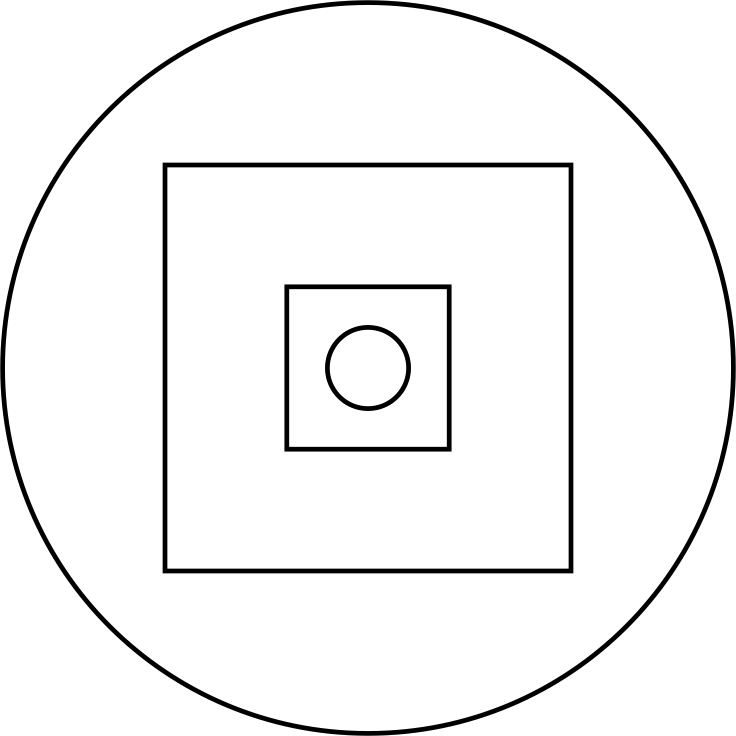

The above is, at least theoretically, not difficult to understand. And still is with this the core of Heidegger's thought explicated. We see in that very short explication that Heidegger's thought actually consists of two important elements. The first element regards the being as primary and equal origin of the secondary subject and object. And the second element regards the two modes of being of authenticity and unauthenticity, whereby the authenticity is underlying the unauthenticity. This is simply to be shown in a figure such as in figure 1.

Figure 1.

This simple figure consists of two inner figures and two outer figures, or of two circles and two squares. The two inner figures symbolize the subject or the being-there and the two outer figures symbolize the object or the world. The two circles symbolize authenticity and the two squares symbolize unauthenticity. From within to the outside counted we see thus symbolized: The authentic being-there, the unauthentic being-there, the unauthentic world and the authentic world. In an authentic mode of being are an authentic being-there and an authentic world equal-original contained, and in an unauthentic mode of being an unauthentic being-there and an unauthentic world. The authentic mode of being is thus symbolized by the two circles and the unauthentic mode of being by the two squares. The arrangement of the circles as inner and outer figures with the squares in between symbolizes that the authentic mode of being regards the outermost possible mode of being that usually is concealed by an unauthentic mode of being. The authentic being-there is placed more central than the unauthentic being-there and the authentic world is wider than the unauthentic world. (In this we can think among others of Heidegger's term 'being-in-whole' [Seiende im Ganzen'] that is equal-original with an authentic being).9

Further details of Heidegger's thought shall here not be worked out. Diverse contemplations with detailed elaborations have been published earlier. In studying these can however this contemplation with the above sketched symbol serve as a guideline.

Notes

- Martin Heidegger, Sein und Zeit, 1927, Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen, 1967, p. 47. "Person ist kein dingliches substanzielles Sein. […]. Die Person ist kein Ding, keine Substanz, kein Gegenstand."

- Ibidem, p. 6. "Das Sein des Seienden »ist« nicht selbst ein Seiendes."

- Gert-Jan van der Heiden, Disclosure and Displacement. Truth and Language in the Work of Heidegger, Ricoeur, and Derrida, Proefschrift, Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen, 2008, p. 15. "Heidegger's central critique of the metaphysical tradition is that it interprets being as a (highest) being, […]."

- Alfred Denker, Historical Dictionary of Heidegger's Philosophy, Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham / London, 2000, p. 221. "Unconcealment is the word Heidegger uses to translate the Greek word for truth, 'alètheia'."

- Sein und Zeit, p. 28. "Als Bedeutung des Ausdrucks »Phänomen« ist daher festzuhalten: das Sich-an-ihm-selbst-zeigende, das Offenbare.

- Walter Biemel, 'Heidegger's Concept of Dasein' in: Frederick Elliston (editor), Heidegger's Existential Analytic, Mouton Publishers, The Hague / Paris / New York 1978, p.112. "In his chief work Being and Time Heidegger avoids the concepts I, subject, person, consciousness, man. Instead of these we find the concept Dasein."

- Sein und Zeit, p. 54. "In-Sein ist demnach der formale existenziale Ausdruck des Seins des Daseins, das die wesenhafte Verfassung des In-der-Welt-seins hat."

- Ibidem, p. 203. "»Welt« ist mit der Erschlossenheit von Welt je auch schon entdeckt. Allerdings kann gerade das innerweltliche Seiende im Sinne des Realen, nur Vorhandenen noch verdeckt bleiben."

- Edward Witherspoon, 'Logic and the Inexpressible in Frege and Heidegger', in: Hubert Dreyfus, Mark Wrathall, Heidegger Reexamined. Volume 4. Language and the Critique of Subjectivity, Routledge, New York, London, 2002, p. 196. "Heidegger uses the term "world" for the totality within which Dasein locates itself and encounters other entities. So we can say that Dasein 's understanding of the world makes it possible for Dasein to encounter any particular entity. Because Dasein understands the totality of entities [das Seiende im Ganzen], Dasein can perceive, think about, and talk about particular entities."

Bibliography

- Walter Biemel, 'Heidegger's Concept of Dasein' in: Frederick Elliston (editor), Heidegger's Existential Analytic, Mouton Publishers, The Hague / Paris / New York 1978.

- Alfred Denker, Historical Dictionary of Heidegger's Philosophy, Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham / London, 2000.

- Martin Heidegger, Sein und Zeit, 1927, Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen, 1967.

- Gert-Jan van der Heiden, Disclosure and Displacement. Truth and Language in the Work of Heidegger, Ricoeur, and Derrida, Proefschrift, Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen, 2008.

- Edward Witherspoon, 'Logic and the Inexpressible in Frege and Heidegger', in: Hubert Dreyfus, Mark Wrathall, Heidegger Reexamined. Volume 4. Language and the Critique of Subjectivity, Routledge, New York, London, 2002.